The Basques are the only Pre-Roman people of the Iberian peninsula that survived the Roman conquest (centuries 3rd-1st B.C.) and the Indo-European expansion (about 2500 B.C.), from whom most of the present-day Europeans descend.

According to the theories supported by a great number of anthropologists and historians, the Basque culture would be the direct descendant of the prehistoric Franco-Cantabrian civilization that extended throughout the northern third of the Iberian peninsula and the southern half of France. Therefore, they are the most ancient people in the old continent.

The history of the Basques began in a territory that we call today Navarre. The Greco-Roman geographers named the land of the Navarreses 'Vasconia' and its inhabitants were known as 'Vascones', from which the current term 'Basque' derives.

Navarre, 'the land of

those who live in the plain situated among the mountains' (that is what the place-name means) was the cradle of the 'lingua navarrorum' (language of the Navarreses) or Basque language as well as the culture that arose beside it.

Navarre, 'the land of

those who live in the plain situated among the mountains' (that is what the place-name means) was the cradle of the 'lingua navarrorum' (language of the Navarreses) or Basque language as well as the culture that arose beside it.

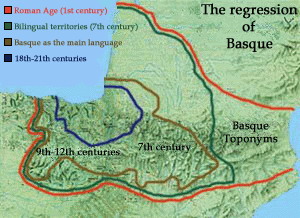

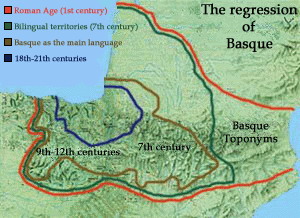

When the Roman empire collapsed during the Frankish-Visigothic age (centuries 5th-8th A.D.), the Vascones of Navarre led the rest of the Basque tribes against the Germanic invaders, what made them become a unique people that have remained until present times. Thereafter, and as a result of this Vascon assimilation, the different tribes disappeared from the texts and arose the use of the term 'Vascones' to refer to them all. The territory of Vasconia extended only through Navarre, La Rioja and northwest Aragon in the Roman imperial period. After the union of the whole Basque tribes, under the lead of the Vascones during the Germanic invasions, the territory enlarged to wider areas in the Pyrenees and southwest France. The Basque term that was used to refer to the Latin place-name 'Vasconia' was 'Euskal Herria' . In the same way, the term 'euskaldunak' was the name that the inhabitants gave themselves. Both names are used today in the Basque speech, while those terms have evolved or changed in other languages throughout history.

During the Frankish-Visigothic age, the Basques were named 'Vascones' as we have mentioned above (also written as 'wascones'). Afterwards, the Carolingian Chronicles began to differentiate the Vascones under Frankish control from the rest, to whom they named 'Navarreses' (the term 'Vascon' would later evolve to the current 'Gascon' ).  The use of the term 'Navarreses' to refer to the Basques became widespread in the 11th century, during the growth of the Kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera (the realm would not officially be named as the Kingdom of Navarre until the following century) while the word 'Vascon' fell gradually into disuse. In the course of the 12th century, the Castilian military expansionism forced the Navarrese realm to renounce the territories of La Rioja and Biscay. At that time, La Rioja was the most important Basque-populated area and its main city Nájera, which was the capital of the realm in that period, was annexed by Castile. Therefore, the capital of the Navarrese kingdom was moved again to Pamplona, the historical Vascon capital.

The use of the term 'Navarreses' to refer to the Basques became widespread in the 11th century, during the growth of the Kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera (the realm would not officially be named as the Kingdom of Navarre until the following century) while the word 'Vascon' fell gradually into disuse. In the course of the 12th century, the Castilian military expansionism forced the Navarrese realm to renounce the territories of La Rioja and Biscay. At that time, La Rioja was the most important Basque-populated area and its main city Nájera, which was the capital of the realm in that period, was annexed by Castile. Therefore, the capital of the Navarrese kingdom was moved again to Pamplona, the historical Vascon capital.

In relation to Biscay, it was ruled by the Otsoitz (López) dynasty, latter known as Otsoitz-Haro (López de Haro). They were put in charge of the territory by the Navarrese monarchy in the 11th century (firstly as a non-hereditary county and latter as a hereditary lordship) and about 1116, the house of Haro was removed by Alfonso I the Battler, king of Aragon and Pamplona. As the Haros were not interested at all in losing power, their ambition led them up to cooperate with Castile in the annexation of Biscay, as well as La Rioja. The services provided by the House of Haro would soon be rewarded by the Castilian Crown with the Lordship of Biscay that they had lost fifty four years before. This new situation made Biscay immerse itself in several wars to defend the Castilian interests, what made the territory enlarge at the same time thanks to the new lands that were received from the Castilian kings. The Lordship of Biscay remained legally independent in the Castilian area of influence until 1516, when it was definitely annexed to Castile.

The services provided by the House of Haro would soon be rewarded by the Castilian Crown with the Lordship of Biscay that they had lost fifty four years before. This new situation made Biscay immerse itself in several wars to defend the Castilian interests, what made the territory enlarge at the same time thanks to the new lands that were received from the Castilian kings. The Lordship of Biscay remained legally independent in the Castilian area of influence until 1516, when it was definitely annexed to Castile.

Throughout the wars carried out by the Castilian realm, the Biscayans became famous by being combatives. This feature would make Basques be known in Castile as 'Biscayans' in the future, and not only in that realm, but in other European countries at that time. On the contrary, the territories of the Aragonese Crown kept on using the term 'Navarreses' to refer to them.

In the 16th century it was common practice to use the term 'Biscayans' to refer to the Basques from both sides of the Pyrenees (except the Lower Navarreses, that were denominated as 'Basques' by France and Spain), as shown in the texts written by Cervantes. In the same century, under the reign of Philip II and during the height of the Spanish Empire, the Basques monopolised the Spanish court administration, as well as the colonies of the empire. During this period, there was a widespread association of concepts that were historically wrong, which linked Basques, Cantabrians and Iberians. According to this, the Basque culture and language were considered the Spanish original ones, and the Basque fueros as the ancestral laws of the Spaniards. Those laws should be respected and safeguarded by the Spanish monarchy in its role of the greatest exponent of Spanishness. The Basques represented the essence of Spain, the indomitable Spain, the Cantabrians that were never conquered even by the Roman Empire. As proof for those erroneous beliefs of the time, there was the thousand-year-old Basque language that was still spoken. The association between the Spanish and the Basque concepts reached such a level that even the royal chronicler Esteban de Garibai (Guipúzcoa) carried out the genealogy of Phillip II, in which the ancestors of the king were linked to the unconquered Cantabrians as well as the Spanish monarchy to the Cantabrian people from the Roman period. The aim of the chronicler was to show a historical reality in which the Spaniards were born to subdue other peoples, but to never be subdued.

The European maps of the 18th century still names current Euskadi as 'Biscay'. The Spanish maps of that period show Biscay as a territory that not only included the present-day territories of Euskadi, but also La Rioja and the eastern half of Cantabria up to the Bay of Santander, since the inhabitants of those areas were considered as Biscayans. The different nouns for the Basques depending on the regions ('Biscayans' for the Castile realm as well as other European countries and 'Navarreses' for the territories of the old Aragonese crown) would still remain valid until the 18th century.

From the 15th and 16th centuries onwards and as a consequence of the wrong association between the Cantabrians from the Roman period and the Basques as noted above, it was common to use the term 'Cantabrian' to designate the Navarreses in the European scholar circles. Since the 16th century, this denomination was also used to designate the western Cantabrians, Biscayans, as well as the people from Álava, Guipúzcoa and La Rioja. This increase of meaning that the scholars of the time gave to that denomination would later give rise to the Basque-Cantabrian theories.

In relation to the spoken language, the Spanish term 'Vascongado' was used to describe those who spoke Euskara (Basque language) until the 17th century. Since the following century, several terms would change their meaning due to the new concepts given by the supporters of the Basque-Cantabrian theory and the Spanish monarchy. Therefore, the term 'Vascongado' changed to mean 'western Basque inhabitant' and 'Vascongadas' to refer to the provinces of Alava, Guipúzcoa and Biscay (present-day Euskadi or Western Basque Country). As we can see, the new meanings  excluded the Navarreses. The origin of the word 'Vascongado' was the Latin term 'vasconicatus' and according to the above-mentioned definition, it was used to refer to the people that spoke Basque, in contrast to 'Romanzado' (from the Latin term 'romanicatus'), which described the speakers of Latin languages. In the past, both terms were used not only in Euskadi, but in Navarre as well.

excluded the Navarreses. The origin of the word 'Vascongado' was the Latin term 'vasconicatus' and according to the above-mentioned definition, it was used to refer to the people that spoke Basque, in contrast to 'Romanzado' (from the Latin term 'romanicatus'), which described the speakers of Latin languages. In the past, both terms were used not only in Euskadi, but in Navarre as well.

In 1587, seventy five years after the Castilian conquest of the Kingdom of Navarre, the Bishopric of Pamplona made a list of population centres. It showed a total number of 536 towns at that time, from which 453 (85% of them) were of Basque speech while the remaining 83 villages (15%) belonged to the Romance speech. Since the Castilian conquest of 1512 and the resulting annexation of the peninsular Navarre to the Castilian crown (1515), a heavy process of loss of the Navarrese identity began, what caused that today only the 20% of the whole Navarrese population is able to speak and/or understand the language that was spoken by their kings. The loss of the Navarrese culture began in the Ebro riverbank and bordering areas of the present-day Aragon, that were under Arab rule. Those territories firstly belonged to the upper March of Al-Andalus, that was ruled from Zaragoza and later under the Hayibate of Zaragoza. Due to this situation, the Basque culture was gradually displaced by the Aragonese culture, which was the most important in the Muslim-ruled territories.

In the 12th century, the Navarreses reconquered the Ebro Riverbank from the Muslims, where Aragonese was the main language and Euskara still kept the second place. The bilingualism of the Riverbank population from that time was expressed in several texts of the 14th century, in which people from native families of the Riverbank are mentioned. A part of this population had a special feature at that time, what proves that there were Basque-speakers: they still professed the Muslim religion and their names were made up of a Muslim first name and a Basque nickname. Since the 14th century, the Aragonese culture of southern Navarre would gradually be assimilated by the Castilian culture, due to the growing political and commercial power of Castile. This process would give rise to the current Castilian-Aragonese culture. Since the 16th century under the Spanish rule, this culture began to spread to middle and north of Navarre, what made their own Basque culture lose ground at the same time.

In the 12th century, the Navarreses reconquered the Ebro Riverbank from the Muslims, where Aragonese was the main language and Euskara still kept the second place. The bilingualism of the Riverbank population from that time was expressed in several texts of the 14th century, in which people from native families of the Riverbank are mentioned. A part of this population had a special feature at that time, what proves that there were Basque-speakers: they still professed the Muslim religion and their names were made up of a Muslim first name and a Basque nickname. Since the 14th century, the Aragonese culture of southern Navarre would gradually be assimilated by the Castilian culture, due to the growing political and commercial power of Castile. This process would give rise to the current Castilian-Aragonese culture. Since the 16th century under the Spanish rule, this culture began to spread to middle and north of Navarre, what made their own Basque culture lose ground at the same time.

Finally, the current term 'Basque' began to spread from the 19th century onwards and comes from the French word 'basque'. This denomination was used during the late Middle Ages and only to refer to the continental Navarreses on the other side of the Pyrenees. The meaning of the 19th-century term 'Basque' was more generic and similar to the Basque denomination 'euskalduna', and made reference to the whole population of the territory, that is to say, 'Vascongados' (people from Álava, Guipúzcoa and Biscay), Navarreses and Basques from the French area.

The Basque world in the Middle Ages, as we will know through the following web pages, was subdivided into different political entities, which included a great part of the Pyrenean area. Nowadays, there are only seven provinces that have kept their original culture: Alava, Lower Navarre, Guipúzcoa, Labourd, Navarre, Soule and Biscay. The dismemberment of both political entities that historically had united the Basques (the Duchy of Vasconia and the Kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera), due to the military expansionism of the surrounding Latin peoples or inner succession problems, caused the division of the Basque people into different political structures, even in antagonistic positions, what made the Basques fight among themselves in successive wars (Castile against Navarre, France against Spain and so on). Anyway, the sense of belonging to a common land, 'The land of Euskara' or Euskal Herria, was always kept although they were not politically united. This concept was already shown in the first Basque writings of the 16th century, as mentioned by writers of that period from the current Euskadi, Navarre and Northern Basque Country.

The Basque world in the Middle Ages, as we will know through the following web pages, was subdivided into different political entities, which included a great part of the Pyrenean area. Nowadays, there are only seven provinces that have kept their original culture: Alava, Lower Navarre, Guipúzcoa, Labourd, Navarre, Soule and Biscay. The dismemberment of both political entities that historically had united the Basques (the Duchy of Vasconia and the Kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera), due to the military expansionism of the surrounding Latin peoples or inner succession problems, caused the division of the Basque people into different political structures, even in antagonistic positions, what made the Basques fight among themselves in successive wars (Castile against Navarre, France against Spain and so on). Anyway, the sense of belonging to a common land, 'The land of Euskara' or Euskal Herria, was always kept although they were not politically united. This concept was already shown in the first Basque writings of the 16th century, as mentioned by writers of that period from the current Euskadi, Navarre and Northern Basque Country.

The term 'Euskal Herria', as well as the word 'euskaldun' bring us back some centuries ago, when they began to spread among the Basque tribes during the decline of the Roman empire and most of all during the Frankish-Visigothic age (since the 5th century A.D.). At that time, the tribes had to join together against the German invaders just to survive, what gave rise to the present-day Basque people. The French language translated the term 'Euskal Herria' as 'Pays Basque' since the word 'euskal' means both 'of Euskara' (of the Basque language) and 'Basque' (adjective). Later on, the Spanish language acquired the French term 'Pays Basque' and translated it as 'Pais Vasco', which is the current term used to refer to the land of the Basques. The English language did the same and translated it as well as 'Basque Country'.

The lack of unity among the Basques after the death of King Sancho III of Navarre, called 'The Great' (11th century), caused them to remain divided into six political entities: the County of Gascony (under French influence), the Kingdom of Castile, the Kingdom of Aragon, the territories of the current Lérida which remained under the influence of the County of Barcelona, the Muslim realm of Zaragoza and the territories that stayed in the kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera after its dismemberment.

The division of the realm after the death of King Sancho III was absolutely fatal for the Basque language, as the Basques were gradually assimilated by the surrounding Latin population. Therefore, the Basque population became to disappear from the southern half of Gascony, northeast of Castile and east of Cantabria, as well as La Rioja, north of Aragon and northwest Catalonia after centuries of cultural assimilation and language prohibitions, like the one that was imposed in the city of Huesca (north of Aragon) that was in force for three centuries. However, this assimilation met resistance in some areas like La Rioja, which was the most important territory inhabited by Basques before the Castilian conquest and annexation, from a political and economical point of view. As an example of this opposition, it was found that in 1239, the mayor of Oiakastro (known today as Ojacastro, La Rioja) ordered the arrest of a royal guard that had been sent by Castile, because he could not speak Euskara. This fact infringed upon the fueros (special rights) of the city, which required the knowledge of the Basque language. At the present, the Basque population and its language only remain in a ninth part of the territory that was comprised in the 11th century.

|

In this introduction to the origin of the Basques we will refer to the latest scientific works, which have been trying to solve the enigmatic origin of these people. When we attempt to get into it, we meet with the main obstacle of the lack of documents about that age since this origin goes back to remote times before writing.

Several archaeologists and anthropologists like José Miguel de Barandiarán and Telesforo Aranzadi, who have worked on bone remains of the Paleolithic period up to the Neolithic in the eastern Cantabrian area and south of France, point out a continuity of a same human group in the region. This study suggested that the present-day Basques come from the old hunter-gatherers that populated the northern third of the Iberian Peninsula and the south half of France and that gave rise to the Franco-Cantabrian civilization. The fact of that the Basques speak a language isolate, that is to say, with no connections to other known language, has reinforced the theory of an archaic human group that was already settled in this territory since prehistoric ages. The links with other brother-peoples that might have had in the past were inevitably lost. Additionally, it is considered that the settlement of the ancestors of the Basques in the Pyrenean area took place a long time before the arrival of the Iberians to the Iberian Peninsula.

The need to face the lack of written documents made the historians start using new technical methods that are based on genetic studies (mitochondrial DNA) in order to be able to know the shifts of the human groups of antiquity.  This kind of work has given rise to a new discipline known as Archaeogenetics, whose application in prehistoric ages is named Paleogenetics. Dr. Peter Forster, who received his Ph.D. in Biology in 1997 and led the molecular genetics laboratory at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (Cambridge University), carried out several genetic works over different populations of Europe, which were based on mtDNA. The results allowed to obtain some maps of the human migrations that took place in Europe throughout the centuries. The McDonald Institute got results that later were confirmed by other similar research works that were carried out by the universities of Oxford and Milan, in which mtDNA (maternal lineage) was not only studied, but also the chromosome Y (father line). Other studies about prehistorical climatology support the research as well since the different human groups migrated or remained in certain areas depending on the climatic conditions.

This kind of work has given rise to a new discipline known as Archaeogenetics, whose application in prehistoric ages is named Paleogenetics. Dr. Peter Forster, who received his Ph.D. in Biology in 1997 and led the molecular genetics laboratory at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (Cambridge University), carried out several genetic works over different populations of Europe, which were based on mtDNA. The results allowed to obtain some maps of the human migrations that took place in Europe throughout the centuries. The McDonald Institute got results that later were confirmed by other similar research works that were carried out by the universities of Oxford and Milan, in which mtDNA (maternal lineage) was not only studied, but also the chromosome Y (father line). Other studies about prehistorical climatology support the research as well since the different human groups migrated or remained in certain areas depending on the climatic conditions.

According to these paleogenetic works, the Cro-Magnon people (our direct ancestors, the first early modern humans who replace the Neanthertals) were scattered all over Europe. Nevertheless, the few ones that could survive the last glaciation 20.000 years ago, had found a shelter in the warmest areas of the continent (northeast and southwest France, as well as Ukraine). During this period, the Franco-Cantabrian civilization arose throughout the northern third of the Iberian peninsula and the southern half of France. Since 16.000 B.C., the climate became warmer and the Proto-Basque population began to spread out across the deserted Europe, taking with them their culture: the Magdalenian.

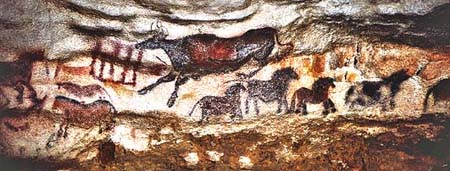

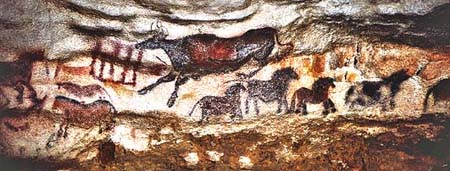

According to these paleogenetic works, the Cro-Magnon people (our direct ancestors, the first early modern humans who replace the Neanthertals) were scattered all over Europe. Nevertheless, the few ones that could survive the last glaciation 20.000 years ago, had found a shelter in the warmest areas of the continent (northeast and southwest France, as well as Ukraine). During this period, the Franco-Cantabrian civilization arose throughout the northern third of the Iberian peninsula and the southern half of France. Since 16.000 B.C., the climate became warmer and the Proto-Basque population began to spread out across the deserted Europe, taking with them their culture: the Magdalenian.  The maximum expression of this culture was with no doubt the cave paintings, which the Proto-Basques decorated the caves with. The extension and location of this culture in Europe match exactly with the above-mentioned research. In addition to this, there have been found phonetic and lexical features that are common to the Basques all through the areas in which the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization flourished, what seems to support the research as well.

The maximum expression of this culture was with no doubt the cave paintings, which the Proto-Basques decorated the caves with. The extension and location of this culture in Europe match exactly with the above-mentioned research. In addition to this, there have been found phonetic and lexical features that are common to the Basques all through the areas in which the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization flourished, what seems to support the research as well.

The melting of the Scandinavian glaciers began 10.000 years ago, what allowed the Proto-Basques spread through that region. The genetic research carried out in the knowledge of the human evolution in Europe, shows that three quarters of the present-day Europeans descend matrilineally (mother line) from a pre-glacial population, who are closely related to the Basques. It also points out that the non-Proto-Basque genetic contribution (Indo-European for the most part) means only the 25%. On the other hand, the study emphasises that the Proto-Basque diffusion, which began 16.000 years ago, not only took place in central, northern Europe and the British Islands, but also in the north of Africa (mainly in Morocco, north of Algeria and Tunisia). Perhaps this fact can help the philological community to throw light on the enigmatic similarities that have been found between Euskara (Basque language) and the Hamitic languages of the north of Africa like Berber, which might have arisen due to the mixing between the Proto-Basques that had settled down in Africa and the Hamitic human groups.

The Indo-Europeans (of whom the present-day Latins, Germanics, Slavs, Celts, Greeks and others are descendants) arrived in western Europe about 2.500 B.C. (according to the warlike expansion theory) or 4.500 B.C. (agricultural expansion theory).

The 'warlike expansion theory' relates the Indo-European invasion from the steppes of northern Ukraine and Russia. The key to this expansion was the use of the horse as a mount, although as some historians indicate today, it could be due to a rise in the Black sea level. This would have been caused by the Mediterranean, when it invaded the basin of the former lake and turned it into a sea. This theory is favoured by Linguistic Archaeology, that is to say, the verification about the fact that there scarcely are agricultural or metallurgical terms in the common Indo-European language, but that there are livestock terms, what would match a pre-agricultural people that came from the then backward Europe. Furthermore, the kind of nouns of flora and fauna that have been rebuilt in this language is closer to the north of Europe than to the tropical areas.

|

The 'agricultural expansion theory', which counts on less supporters, holds that the Indo-European invasion would have begun on the Asian Turkey, taking along with it the agriculture. The explanation does not fit with what Linguistic Archaeology proposes, but it counts on the research of the Italian-American geneticists Cavalli-Sforza, who deduces that an ancient shift of population towards Europe took place from that Turkish area. The Indo-European people, who were more advanced in war technology than the rest of the non-Indo-Europeans, were able to subjugate most of the population that inhabited Europe until then, what caused the extinction of their languages and cultures. Across those turbulent ages, Euskara (Basque language) could survive and stayed as the only linguistic vestige of the pre-Indo-European past.

During the Roman age, there were the following Basque tribes that survived the Indo-European diffusion in the west of Europe: Aquitani, Autrigones, Caristii, Varduli and Vascones that were placed on both sides of the Pyrenees. Some historians consider the Berones of La Rioja as another Basque tribe, while others think that they were Celtiberians (the different Celtic peoples  that inhabited the Iberian peninsula). The bone studies that have been carried out at archaeological sites in the Basque Cantabrian area and Gascony, reveal that the racial features of the inhabitants in this region during Neolithic belonged to what Anthropology denominates Western-Pyrenean type or Basque (a local evolution of the Cro-Magnon man), while the population to south of the Basque Country (southern Alava and Navarre) and the Berones territory were very heterogeneous, with people from different European origins (Mediterraneans, Alpines, Dinarics...). At this point, it is difficult to connect the Berones to a Basque origin, although the Basque-speech ethnic groups had already taken control of the southern territories at the arrival of the Romans. The study of their anthroponyms (names of human beings) of that period denotes as well a Celtic origin.

that inhabited the Iberian peninsula). The bone studies that have been carried out at archaeological sites in the Basque Cantabrian area and Gascony, reveal that the racial features of the inhabitants in this region during Neolithic belonged to what Anthropology denominates Western-Pyrenean type or Basque (a local evolution of the Cro-Magnon man), while the population to south of the Basque Country (southern Alava and Navarre) and the Berones territory were very heterogeneous, with people from different European origins (Mediterraneans, Alpines, Dinarics...). At this point, it is difficult to connect the Berones to a Basque origin, although the Basque-speech ethnic groups had already taken control of the southern territories at the arrival of the Romans. The study of their anthroponyms (names of human beings) of that period denotes as well a Celtic origin.

The wrong consideration of the surrounding tribes as Basques was repeated this time with the Iacetans of Huesca, what later was solved by further studies. However, we should remember that the Basque population coexisted with Celts and Iberians all over the Pyrenean area. Due to the alliance of the peninsular Basque tribes and Rome, the lands that had been conquered to Cetiberians and Iberians were later repopulated with Basque-speech people. The fact that the cities and lands of the western Pyrenees, western Zaragoza as well as La Rioja and northeastern Castile were already listed as Basques during the Roman imperial age has contributed to the above-mentioned mistake, when part of the land belonged in fact to Celtiberian or Iberian tribes before the Roman conquest. This alliance among the Basque tribes and Rome against their common enemies was the main reason by which the Basque culture is the only Pre-Roman one that survived the expansion of Rome. A secondary reason for  this survival was the belated development of the Mare Externum (Atlantic Ocean) as an interesting economical source to the Empire, what allowed the region to be apart from the strong migratory flows that took place in other areas of the peninsula or in Aquitaine, due to its agricultural possibilities.

this survival was the belated development of the Mare Externum (Atlantic Ocean) as an interesting economical source to the Empire, what allowed the region to be apart from the strong migratory flows that took place in other areas of the peninsula or in Aquitaine, due to its agricultural possibilities.

When the Celts arrived in the current Navarre, approximately in the 8th century B.C., they named the inhabitants of the Pyrenean area with the term 'barskunes' or 'baskunes' (highlander). The Celts settled in the plains of central and southern Navarre and influenced the culture of the population, who belonged to different ethnic groups (Mediterraneans, Archaics, Alpines or Dinaric-Armenians). Later, a new culture settled along the Ebro river and prevailed over the Celts: the Iberian culture. In that way, the central and southern areas of Navarre got into a celtization and iberization process, from which the northern Baskunes remained apart. Since the 3rd century B.C. the Baskunes began to spread southwards and took control of the plain lands of Navarre, what allowed them to influence the former population. The mixing of Baskunes and the different ethnic groups that lived in the above-mentioned area caused the emergence of a tribe that integrated many Celtiberian and Iberian customs and usages that would later take part in the Baskun tradition The Basque religion, of prehistoric origin and with many similarities to the ancient Minoan religion of Crete, went on evolving and enlarging its worship elements and rituals by means of the Iberian and Celtic influence:

The worship of the Sun and the Moon was of great importance for the Basque religion, the same as in the Celtic or Iberian traditions. The Sun was the cosmic representation of Mari, the supreme goddess, while the Moon enlightened the path to the Underground World where the dead would live with their ancestors and the goddess for eternity. The old usage of the lunar cycle as a time measure handed us down terms like 'hilabete' (month), which literally means 'full moon'. There is also 'aste' (week), that meant 'the lunation beginning'. It is probably that ritual dances in honour of both goddesses Moon and Sun were performed since they were daughters of Mari (the sun was feminine in the Basque culture). The worship of rivers, mountains, trees or the forest, which were typical of Celtic cultures, took part of the Baskun tradition as well.

The government was established by means of a council of elders, just the same as in the Iberian costumes although this system was common to many ancient civilizations. On the other hand, the Baskunes used to choose a war chief among the notables of the tribe, like in the Celtiberian tradition. Along the same line, the Celtic war chiefs should belong to one of the highest castes of the tribe. In relation to the field of divination, the Baskunes also had magicians and augurs, like the Iberians and the Celts respectively. The Baskun augurs were able to predict the future by watching the flight of the birds in the sky. Thus, at present, the Basques use the term 'zorionak' to congratulate someone, as it means etymologically 'good birds'. The practice of foreseeing the future was carried on across time since we know that during the Roman age, Vasconia and Pannonia were  the territories of the Empire that had the best augurs, to whom the emperor used to request for advice.

the territories of the Empire that had the best augurs, to whom the emperor used to request for advice.

The idol of Mikeldi (Durango, Biscay) dates of the Iron Age (4th-3rd B.C.). It represents a bull or boar that has a disc among its paws, whose both faces mean the Sun and the Moon. The sculpture symbolises the goddess Mari or 'Mother Earth', who shelters her celestial daughters when they set on the 'Reddish Seas' (Itsasgorrieta) and follow their course through the Underground World.

The Baskunes, who inhabited the area that goes from the Pyrees to Pamplona, lived off cattle rising and a subsistence economy based on hunting and gathering. The agriculture was introduced in the plain lands of the southern half of Navarre by the different ethnic groups that inhabited the area, as we have mentioned above. The population underwent some culture changes, as they were firstly celtizied, later they were iberized and finally 'baskunized' since the 3rd century B.C.. The Celts introduced several new types of cultivation in Navarre, although they were not carried out on a large scale. The cattle raising and hunting were also usual tasks in the plain lands, just the same as in the northern half of the territory. The tribal organization that prevailed in the south of Navarre was similar to the ones that ruled other areas of the Iberian peninsula since there was an aristocracy inherited from the tribal system of the Celtic invaders. However, the economic system that was carried out at that time would be changed during the arrival of the Romans in the 2nd century B.C.. They adapted the Celtic term 'Baskunes' to their language and turned it into 'Vascones', a term that would endure through time until the Middle Ages, when it was substituted by the term 'Navarreses'. Some researchers consider that this term (which was pronounced 'uascones' in Latin), does not come from the Celtic term, but it is a Latin adaptation  of the Basque root 'eusk-', which comes in turn from the word 'euskara'.

of the Basque root 'eusk-', which comes in turn from the word 'euskara'.

About the III century B.C., the tribe of the Vascones began an expansion process from the north of Navarre (Saltus Vasconum or mountainous area of Navarre), which made its language be spoken in the 6th century A.D. from part of Cantabria (west) to part of Catalonia (east); northwards up to the Garonne (half of the present France) and southwards, up to the Ebro river. This expansion was developed according to the brief description below:

In the course of the 3rd-2nd centuries B.C., the Vascones expanded eastwards up to part of Catalonia, where coexisted with Celtiberians and Iberians. During the Roman Age and thanks to the good relationship that the Basque tribes and especially the Vascones, had with Rome, a great number of cities of La Rioja, northeast of Castile, south of Navarre as well as north and west of Aragon were shown in writings as ruled by the Basques after the Roman conquest, when they were Celtiberians or Iberians at the beginning of the occupation. Several cities like Calagurris (Calahorra, La Rioja), Cascantum (Cascante, south of Navarre) and Graccurris (Alfaro, La Rioja, founded by the Romans) were Celtiberians before the conquest, but later, under the Empire, they were listed as Vascon towns. About the 1st century A.D., the Greek geographer Strabo described in his writings that the main Vascon cities were Calagurris, Pompaelo (Pamplona) and Oiasso (Irún, Guipúzcoa). In the same way, Iaca (Jaca, Huesca. Northern Aragon) and Segia (Egea de los Caballeros, Zaragoza. Western Aragon) that belonged to the Iacetani and Suessetani respectively, remained under Vascon rule after the Roman intervention. In the 3rd century A.D., during the decline of the Roman Empire, the Basque tribes began to join themselves, what caused in time the development of Common Euskara. This process was accelerated during the Germanic invasions since the Vascones led the rest of the tribes against the new conquerors. From that period onwards, any reference to the Basque tribes disappeared and arose the term 'Vascones' to mention them all as a unique people.

As a consequence of the Visigothic raids in the 6th century A.D., the Vascones of Euskadi, Navarre, Aragon, Andorra and Catalonia settled in the territory of Novempopulania ('Country of the Nine Peoples', southwest France), taking advantage of  the weakness and chaos caused by the war between Visigoths and Franks that left the area unprotected. Therefore, Common Euskara of the Late Roman Imperial age spread throughout southwest France up to Bordeaux (Garonne river) and southwards, up to the current French-Spanish border at Lleida.

the weakness and chaos caused by the war between Visigoths and Franks that left the area unprotected. Therefore, Common Euskara of the Late Roman Imperial age spread throughout southwest France up to Bordeaux (Garonne river) and southwards, up to the current French-Spanish border at Lleida.

At the present time, we can find many Basque toponyms further south than the current Basque limits:

To the southwest of the territory, along the Oca Mountains (Oka Mendiak), the region of La Bureba and the Valley of Mena in the province of Burgos, as well as La Rioja and Soria (Oria). All these lands were later turned into Basques once more during the first years of the Reconquest, what made Castile be a Basque-speech territory for the most part at the beginning of its establishment. In any case, Burgos and La Rioja were Basque-speakers since Pre-Roman times until the 15th-16th centuries, when Castilian (12) displaced Euskara after some centuries of bilingualism.

(12) Castilian or Spanish: it is the language that emerged during the Reconquest. Its origin is found in the speech of the Romanised Basques of Cantabria, the north of Burgos, the adjacent western strip of Alava and the Biscayan region of Las Encartaciones. In the Roman age, these lands were inhabited by the most western Basque tribe: the Autrigones. Due to their proximity to the Plateau, which was a focus of the new technology and customs since the Neolithic, Latin and the Roman culture entered their territory and spread more strongly. According to this, the Castilian people and its language arose as a consequence of the romanisation process of the Autrigones.

The first written evidence of the Castilian language was the Cartularies of Santa María de Valpuesta (Burgos). The manuscri pts of this monastery date from the years 804-1200 and they were written as copies of the original documents from the archives of the Crown, localities, bishoprics, monasteries, churches and individuals with reference to property deeds, privileges, rights and other legal documents. The purpose of the copies was their usage in case of loss of the original documents, so that any institution or individual could prove their rights. These first texts already show certain words with sounds that belong to Castilian romance although a strictly Castilian text was not found until the year 1200.

pts of this monastery date from the years 804-1200 and they were written as copies of the original documents from the archives of the Crown, localities, bishoprics, monasteries, churches and individuals with reference to property deeds, privileges, rights and other legal documents. The purpose of the copies was their usage in case of loss of the original documents, so that any institution or individual could prove their rights. These first texts already show certain words with sounds that belong to Castilian romance although a strictly Castilian text was not found until the year 1200.

The Cartularies, the same as the Glosses of Saint Emilianus of San Millán de la Cogolla (first evidence of the Aragonese Romance), show many terms and names of Basque origin: Anderkina ('little lady'), Enneco ('my little (child)', from which the Castilian name Iñigo derives), Ozoa ('the wolf', from which the Castilian surname Ochoa derives). There are also Basque expressions like mie ennaia ('my brother'), as well as related terms: eita ('father'), ama ('mother'), ennaia ('brother'), amunnu ('grandmother') ... Modal terms are also found like Anderazu ('elder lady', similar to the current term 'Mistress' which also appears in several texts of La Rioja from the 11th century). The manuscripts include as well some Basque local place-names: Margalluli, Yrola, Zopillozi ... It is amazing to find out that after ten centuries and in the areas of the Basque Country whose culture has been gradually assimilated by Castilian, there are daily expressions that ha ve been kept very similar to the ones used by the former Castilians: mi aita ('my father'), mi ama ('my mother').

ve been kept very similar to the ones used by the former Castilians: mi aita ('my father'), mi ama ('my mother').

The Asturian eastward expansion and the inclusion of the territory (that would later be Castile), in the Kingdom of Asturias made many Asturian colonists settle in the new conquered lands of eastern Cantabria and northern Burgos, what boosted the latinisation process. At this point, there are two interesting questions to be valued: on the one hand, the very first Castilian evidence was similar to the one of the Astur-Leonese language and on the other hand, the Castilian most genuine names and surnames were of Basque origin. Both matters make some historians think of that the romanisation of the territory was very poor before the arrival of the Asturian colonists and that the copyist, who wrote the first texts, was not Castilian, but Asturian. Note that Euskara was still spoken all over the northwest area of the province of Burgos in the 11th century up to the Arlanzón river, near the city of Burgos, as this area was inhabited by Basques since Pre-Roman ages. It is known as well that the Visigoths used the castle of Tedeja (Trespaderne, Burgos) as a vanguard position in the Vascon front during the 5th century.

This initial Romanized Castilian that is shown on the cartularies was very similar to the present eastern dialect of the Astur-Leonese language that is spoken in the Cantabrian region of Liébana (e.g. the plural words of the feminine gender end with the suffix -es [Salines] like in Astur-Leonese, instead of-as [Salinas], which is the usual form). This dialect has a strong Basque phonetic influence, characterized by the loss of the 'f' at the beginning of the word in most of the cases and turning its sound in an aspirated 'h' (at the present time it is pronounced as a very strong 'h', which is written with 'j') since the sound 'f' did not exist in Euskara until the Middle Ages, while there was a strong aspiration. This was what caused the phonetic evolution that is also found in the Gascon dialect of Occitan which arose from the romanisation of the Basque-speech population of Aquitaine. In order to explain the Basque substratum of eastern Astur-Leonese that is spoken today in Cantabria and eastern Asturias, there are three theories: the first one considers that there were Basque-type languages spoken throughout the northern half of the Peninsula since prehistoric ages. The second one states that the Cantabrian and Asturian tribes, which are considered Celtic tribes, were in fact Basques. The last one suggests that the substratum was the result of the Autrigones recolonisation of the Cantabrian and Asturian territories after their conquest by Rome.

|

Astur-Leonese |

Eastern Astur-Leonese |

Spanish |

English |

|

Falar |

Jalar |

Hablar |

To speak |

|

Facer |

Jacir |

Hacer |

To make |

|

Latín |

Euskara Spanish |

English |

|

Fundus |

Hondo Fondo |

Bottom |

|

Fornitura |

Hornidura Abastecimiento |

Supply |

During the Reconquest, the province of Burgos became a meeting point for both Astur-Leonese an Aragonese speakers, what influenced the Romance evolution. When this initial language spread southwards, it mixed with Romance that was spoken by the Mozarabs, what gave shape to the current Castilian. This meant the introduction of a great deal of words of Arabic origin and the recovery of the Latin initial 'f' (hebrero>febrero = February; Hernando>Fernando = Ferdinand; hondo>fondo = bottom). The Basque phonetic substratum (in which there are not the rising diphthongs /je/ and /we/) caused the softening of the strong diphthongization of the old Latin stressed vowels 'e' and 'o', which already existed in the central Romances of the peninsula, i.e. Astur-Leonese and Aragonese.

During the Reconquest, the province of Burgos became a meeting point for both Astur-Leonese an Aragonese speakers, what influenced the Romance evolution. When this initial language spread southwards, it mixed with Romance that was spoken by the Mozarabs, what gave shape to the current Castilian. This meant the introduction of a great deal of words of Arabic origin and the recovery of the Latin initial 'f' (hebrero>febrero = February; Hernando>Fernando = Ferdinand; hondo>fondo = bottom). The Basque phonetic substratum (in which there are not the rising diphthongs /je/ and /we/) caused the softening of the strong diphthongization of the old Latin stressed vowels 'e' and 'o', which already existed in the central Romances of the peninsula, i.e. Astur-Leonese and Aragonese.

|

Astur-Leonese |

Spanish |

English |

|

Güey |

Hoy |

Today |

|

Yera |

Era |

|

The Basque substratum provided Spanish with five vowels regardless of any degree (/i/, /e/, /a/, /o/ and /u/) and therefore, turned it into the only Latin language that has only five vowels.  The lack of the voiced labiodental fricative phoneme /v/ in the Spanish phonetics, which is a characteristic of the languages that are spoken in the area of the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization (Galician, Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Gascon, Occitan and Catalonian, with the exception of Valencian) is another feature of this substratum. The above-mentioned phoneme existed in the ancient Castilian although it was not used in the territories of Burgos, Cantabria and La Rioja where the pronunciation of /v/ was the same as /b/. This characteristic became widespread across the time since the language spoken in Burgos was taken as standard Castilian. The Spanish phonetics also shows two trilled phonemes: the simple /r/ and the multiple /rr/, which are opposed in an intervocalic position: /caro/ and /carro/; /moro/ and /morro/. At the initial position only the multiple trilled phoneme can be used. This unique distribution comes from the Basque substratum and it is also a feature of the territories where the Franco-Cantabrian civilization was developed. The Basque phonetics requires as well a prothetic vowel at the beginning of the word (/a/ or /e/), so that the sound /rr/ can be pronounced.

The lack of the voiced labiodental fricative phoneme /v/ in the Spanish phonetics, which is a characteristic of the languages that are spoken in the area of the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization (Galician, Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Gascon, Occitan and Catalonian, with the exception of Valencian) is another feature of this substratum. The above-mentioned phoneme existed in the ancient Castilian although it was not used in the territories of Burgos, Cantabria and La Rioja where the pronunciation of /v/ was the same as /b/. This characteristic became widespread across the time since the language spoken in Burgos was taken as standard Castilian. The Spanish phonetics also shows two trilled phonemes: the simple /r/ and the multiple /rr/, which are opposed in an intervocalic position: /caro/ and /carro/; /moro/ and /morro/. At the initial position only the multiple trilled phoneme can be used. This unique distribution comes from the Basque substratum and it is also a feature of the territories where the Franco-Cantabrian civilization was developed. The Basque phonetics requires as well a prothetic vowel at the beginning of the word (/a/ or /e/), so that the sound /rr/ can be pronounced.

|

Latin |

Euskara |

Spanish |

English |

|

Rationis |

Arrazoi |

Razón |

Reason |

|

Romanicus |

Erromaniko |

Románico |

Romance |

This feature was also typical of the ancient Castilian, where lexical cognates arose and coexisted for a time in the speech with and without epenthesis, like the following examples: ruga / arruga (wrinkle); repentir / arrepentir (to regret), rancar / arrancar (to pull up), rebatar / arrebatar (to snatch).

There are many terms of Basque origin in the Spanish vocabulary. Regarding the surnames of this same origin,

there are shown several examples in the list below. Note that most of them were used as first names during the Middle Ages:

Aznar comes from the medieval Basque term 'Azenari' (fox) or 'Azeari', which comes in turn from the Latin term 'asinarius' (donkey).

Garcia (Gartzia) comes from the eastern Basque 'Gartzea' (the young, the infant), which has the same meaning as the western Basque term 'gaztea'.

Iñigo derives from the name Eneko (my little (child)), which consists of the particles 'Ene' (my) and '-ko' (diminutive).

Jimeno is the adaptation of the name Xemeno (little son), which comes in turn from the term Xeme (diminutive of the word 'Seme' (son) and the particle '-no' (diminutive)).

Lope derives from the medieval Latin term 'Lupo', which was in turn the romance version of the Basque name Otsoa (the wolf). At the present time, it is kept as the Spanish surname Ochoa.

Sancho (Antso in Basque) derives from the Latin noun 'sanctius' (saint). In spite of its non-Basque origin, this name became popular in Vasconia and spread to other territories beyond the ones of Basque influence.

Velasco / Belasco / Blasco, which are Spanish surnames today. They all come from the Basque name 'Belasko' (Little Bela), which is a composition of the name Bela (a phonetic adaptation of the Visigothic name 'Vigila') and the particle -(s)ko (diminutive).

Urraco ('little golden') comes from the term Urre (gold, golden) and the particle -ko (diminutive). This name was better known in its feminine form Urraka, which was a very popular name among the queens of Navarre, the countesses of Gascony and the queens of Castile.

The Latin influence introduced in the Basque language the usage of a same name in both feminine and masculine versions, a costume that did not exist in Euskara since there are no genders in the Basque grammar. Therefore, the transformation of the names into their feminine form were built by changing the final '-o' for an '-a' , so that the resulting names were: Urrako/Urraka, Eneko/Eneka, Xemeno/Xemena or Belasko/Belaska. The Castilian version of these names, as they were romanized Basque terms, remained as follows in their feminine form: Urraca, Iñiga, Jimena or Velasca.

The construction of the Castilian patronymics has also a Basque origin. In Spanish, it is not said 'Fernandes' (as in Portuguese, with the suffix -es), but Hernández (the Castilian most genuine form of this surname) or Fernández (suffix -ez). Euskara built their patronymics using the suffix '-itz' (which comes in turn from the Latin genitive '-is') that became '-iz' when adapting it to Castilian. As the Reconquest advanced southwards, the suffix turned finally into '-ez '. In order to understand this process, let us have a look at the following example with the Basque name Orti (Fortún in Spanish): the patronymic was Ortitz (Fortúnez in Spanish), which evolved to the form Ortiz and that was also acquired by Castilian

The Castilian language got this kind of construction directly from Euskara instead of Latin, unlike the Portuguese case (Fernandes), or the Valencian dialect of Catalonian (Ferrandis). The Latin adaptation of the Basque patronymic construction (suffix '-iz') became very popular throughout the northern third of the Iberian peninsula during the 11th century due to the great influence of the Navarrese monarchy that ruled a vast territory from Galicia to the Mediterranean coast of Catalonia in that period. This is why it is easy to find traces of this name construction in the toponymy of this vast area, even in Galicia.

The writer Gonzalo de Berceo (La Rioja, 13th century), who was one of the first writers that used Castilian in his texts, included Basque words like 'bildur' (fear) with reference to the devil, to whom he named 'Don Bildur'. Other words like 'gabe' (without / deprived of) and the old term 'çatico' which came from the Basque word 'zatiko' (small piece). During the 11th century, the courtesy expressions were of Basque origin for the most part in La Rioja. The usage of the word 'aita' (father) as well as their versions 'acha' (written as agga), 'eita' or 'echa' (written as egga) was common practice to refer to the Castilian terms 'Don' or 'Señor' (Mr.) e.g. 'Eita Gomiz' was the same as the current 'Señor Gómez'. This peculiar usage would give rise to certain toponyms like Chamartín (Don Martín - Mr. Martin) or Chavela (Don Vela - Mr. Vela). The feminine form of 'eita' was 'anderazo' or 'anderazu' ('Doña' or 'Señora' - Mrs/Ms), which came from the Basque term 'andere' (lady) and the particle '-atzo' (elder woman in medieval Euskara.

At the present time, the term 'atso' is used) e.g. Anderazo de Fortes (Señora de Fuertes - Mrs. Fuertes) or Anderazo de Clementi (Señora de Clemente - Mrs. Clemente). Both names are shown in the texts of that period. The texts of La Rioja, include as well other words of Basque origin: annaya (the same as the Basque term 'anaia' (the brother), ama (mother), amunna (grandmother; the same as the western Basque term 'amuña') and finally eigiga (grandfather; the same as the western Basque term 'aitita') The Basque words that were used as forms of social treatment or love for the relatives became proper names (Annaia Ferrero) or even patronymics (Garcia Annaiaz). There were also nicknames like Minaya (my brother), which appears in The Poem of the Cid as the way in which the Cid addressed his relative Alvar Fáñez. There are other compound forms like Miegga (my father) and a mixt of Basque and Romance or Gothic names which resulted in a new name, e.g. Andregoto ('Andre' - lady- and 'Goto' -Gothic origin-), that was a widespread name as much in La Rioja as in Aragon and the rest of the areas of Basque speech at that time.

There are other Basque loanwords in the Castilian vocabulary which refer to garments like abarca (a kind of sandal), boina (beret), chistera (top hat), chamarra or zamarra (jacket). Agricultural terms: cencerro (cow bell), laya or narria (small cart). Nouns of animals, minerals and plants like chaparro (dwarf oak), garrapata (tick, insect), sabandija (creepy-crawly), sapo (toad) or zumaya (a nocturnal bird). Other usual terms: alud (avalanche), aquelarre (witches's sabbath), ascua (ember), azcona (a kind of throwing weapon), baldarra (clumsy), chabola (hut), charro (gaudy), chatarra (scrap), chirimbolo (an object with an imprecise shape and no name), gabarra (flat boat), izquierda (left), mochila (backpack), nava (a plain land in the middle of the mountains), órdago (similar to the expression 'all or nothing'), socarrar (to singe) or zurrón (pouch).

In the Middle Ages, Euskara was still spoken in the following territories:

The Catalonian Pyrenees, in the Aran Valley (the noun 'haran' means 'valley' in Basque) and Andorra (which means 'the land covered with bushes'). The Basque language was spoken in the Pyrenean villages of Lérida until the 12th-13th centuries. Aragon (it means 'the place in the valley') was also a Basque-speech territory, especially the towns of the province of Huesca, as well as the western area of the province of Zaragoza until the 18th century. The capital city of Huesca, of the same name, was called Oska in the past. Since 1349, a law that ensured the prohibition of the language that gave the territory its name came into force and remained valid for three centuries, as proved in the documents of that age. This situation caused the disappearance of the Basque population of the area and the predominance of the Aragonese language.  Euskara was also spoken in the region of Las Cinco Villas de Aragon (province of Zaragoza, to southeast of Navarre) since the pre-Roman age until the 18th century. This was proved by the discovery of Roman inscriptions in Sádaba and Sofuentes in which Basque given names are listed.

Euskara was also spoken in the region of Las Cinco Villas de Aragon (province of Zaragoza, to southeast of Navarre) since the pre-Roman age until the 18th century. This was proved by the discovery of Roman inscriptions in Sádaba and Sofuentes in which Basque given names are listed.

Along the same line, there are documents dated of the 16th and 17th centuries that mention the Basque-speech condition of the current town Sos del Rey Católico (Zauze in Basque) at that time. In this sense, we must emphasise the fact that a great part of the area belonged to the Bishopric of Pamplona until 1785, given its Basque-speaking nature. With regard to La Rioja, Euskara was the language of Nájera, the capital city of the former Kingdom of Pamplona-Nájera during the 10th-12th centuries. The monastery of Santa María la Real houses the sepulchres of Navarrese kings in its area known as 'Panteón de los Reyes' (The Pantheon of the Kings), what supports the royal condition of the city where the first coin of a Christian peninsular realm was minted in 1034. The reverse of the coins included the name of the city: Naiara (the Basque name of Nájera). Euskara was spoken as well in other places of the province until the 16th century. In relation to the other side of the Pyrenees, the Basque language was used in different villages of Béarn (France) until the 16th century although many of the towns preserved the language until the 19th century. Nowadays, Euskara is spoken in a few bordering cities of this region and its situation is extremely weak.

Share this page!

The History of the Basque Country continues on the following page >> Prehistory

The maximum expression of this culture was with no doubt the cave paintings, which the Proto-Basques decorated the caves with. The extension and location of this culture in Europe match exactly with the above-mentioned research. In addition to this, there have been found phonetic and lexical features that are common to the Basques all through the areas in which the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization flourished, what seems to support the research as well.

The maximum expression of this culture was with no doubt the cave paintings, which the Proto-Basques decorated the caves with. The extension and location of this culture in Europe match exactly with the above-mentioned research. In addition to this, there have been found phonetic and lexical features that are common to the Basques all through the areas in which the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization flourished, what seems to support the research as well.

that inhabited the Iberian peninsula). The bone studies that have been carried out at archaeological sites in the Basque Cantabrian area and Gascony, reveal that the racial features of the inhabitants in this region during Neolithic belonged to what Anthropology denominates Western-Pyrenean type or Basque (a local evolution of the Cro-Magnon man), while the population to south of the Basque Country (southern Alava and Navarre) and the Berones territory were very heterogeneous, with people from different European origins (Mediterraneans, Alpines, Dinarics...). At this point, it is difficult to connect the Berones to a Basque origin, although the Basque-speech ethnic groups had already taken control of the southern territories at the arrival of the Romans. The study of their anthroponyms (names of human beings) of that period denotes as well a Celtic origin.

that inhabited the Iberian peninsula). The bone studies that have been carried out at archaeological sites in the Basque Cantabrian area and Gascony, reveal that the racial features of the inhabitants in this region during Neolithic belonged to what Anthropology denominates Western-Pyrenean type or Basque (a local evolution of the Cro-Magnon man), while the population to south of the Basque Country (southern Alava and Navarre) and the Berones territory were very heterogeneous, with people from different European origins (Mediterraneans, Alpines, Dinarics...). At this point, it is difficult to connect the Berones to a Basque origin, although the Basque-speech ethnic groups had already taken control of the southern territories at the arrival of the Romans. The study of their anthroponyms (names of human beings) of that period denotes as well a Celtic origin.  this survival was the belated development of the Mare Externum (Atlantic Ocean) as an interesting economical source to the Empire, what allowed the region to be apart from the strong migratory flows that took place in other areas of the peninsula or in Aquitaine, due to its agricultural possibilities.

this survival was the belated development of the Mare Externum (Atlantic Ocean) as an interesting economical source to the Empire, what allowed the region to be apart from the strong migratory flows that took place in other areas of the peninsula or in Aquitaine, due to its agricultural possibilities. the territories of the Empire that had the best augurs, to whom the emperor used to request for advice.

the territories of the Empire that had the best augurs, to whom the emperor used to request for advice.

the weakness and chaos caused by the war between Visigoths and Franks that left the area unprotected. Therefore, Common Euskara of the Late Roman Imperial age spread throughout southwest France up to Bordeaux (Garonne river) and southwards, up to the current French-Spanish border at Lleida.

the weakness and chaos caused by the war between Visigoths and Franks that left the area unprotected. Therefore, Common Euskara of the Late Roman Imperial age spread throughout southwest France up to Bordeaux (Garonne river) and southwards, up to the current French-Spanish border at Lleida.

During the Reconquest, the province of Burgos became a meeting point for both Astur-Leonese an Aragonese speakers, what influenced the Romance evolution. When this initial language spread southwards, it mixed with Romance that was spoken by the Mozarabs, what gave shape to the current Castilian. This meant the introduction of a great deal of words of Arabic origin and the recovery of the Latin initial 'f' (hebrero>febrero = February; Hernando>Fernando = Ferdinand; hondo>fondo = bottom). The Basque phonetic substratum (in which there are not the rising diphthongs /je/ and /we/) caused the softening of the strong diphthongization of the old Latin stressed vowels 'e' and 'o', which already existed in the central Romances of the peninsula, i.e. Astur-Leonese and Aragonese.

During the Reconquest, the province of Burgos became a meeting point for both Astur-Leonese an Aragonese speakers, what influenced the Romance evolution. When this initial language spread southwards, it mixed with Romance that was spoken by the Mozarabs, what gave shape to the current Castilian. This meant the introduction of a great deal of words of Arabic origin and the recovery of the Latin initial 'f' (hebrero>febrero = February; Hernando>Fernando = Ferdinand; hondo>fondo = bottom). The Basque phonetic substratum (in which there are not the rising diphthongs /je/ and /we/) caused the softening of the strong diphthongization of the old Latin stressed vowels 'e' and 'o', which already existed in the central Romances of the peninsula, i.e. Astur-Leonese and Aragonese.  The lack of the voiced labiodental fricative phoneme /v/ in the Spanish phonetics, which is a characteristic of the languages that are spoken in the area of the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization (Galician, Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Gascon, Occitan and Catalonian, with the exception of Valencian) is another feature of this substratum. The above-mentioned phoneme existed in the ancient Castilian although it was not used in the territories of Burgos, Cantabria and La Rioja where the pronunciation of /v/ was the same as /b/. This characteristic became widespread across the time since the language spoken in Burgos was taken as standard Castilian. The Spanish phonetics also shows two trilled phonemes: the simple /r/ and the multiple /rr/, which are opposed in an intervocalic position: /caro/ and /carro/; /moro/ and /morro/. At the initial position only the multiple trilled phoneme can be used. This unique distribution comes from the Basque substratum and it is also a feature of the territories where the Franco-Cantabrian civilization was developed. The Basque phonetics requires as well a prothetic vowel at the beginning of the word (/a/ or /e/), so that the sound /rr/ can be pronounced.

The lack of the voiced labiodental fricative phoneme /v/ in the Spanish phonetics, which is a characteristic of the languages that are spoken in the area of the ancient Franco-Cantabrian civilization (Galician, Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Gascon, Occitan and Catalonian, with the exception of Valencian) is another feature of this substratum. The above-mentioned phoneme existed in the ancient Castilian although it was not used in the territories of Burgos, Cantabria and La Rioja where the pronunciation of /v/ was the same as /b/. This characteristic became widespread across the time since the language spoken in Burgos was taken as standard Castilian. The Spanish phonetics also shows two trilled phonemes: the simple /r/ and the multiple /rr/, which are opposed in an intervocalic position: /caro/ and /carro/; /moro/ and /morro/. At the initial position only the multiple trilled phoneme can be used. This unique distribution comes from the Basque substratum and it is also a feature of the territories where the Franco-Cantabrian civilization was developed. The Basque phonetics requires as well a prothetic vowel at the beginning of the word (/a/ or /e/), so that the sound /rr/ can be pronounced.

Euskara was also spoken in the region of Las Cinco Villas de Aragon (province of Zaragoza, to southeast of Navarre) since the pre-Roman age until the 18th century. This was proved by the discovery of Roman inscriptions in Sádaba and Sofuentes in which Basque given names are listed.

Euskara was also spoken in the region of Las Cinco Villas de Aragon (province of Zaragoza, to southeast of Navarre) since the pre-Roman age until the 18th century. This was proved by the discovery of Roman inscriptions in Sádaba and Sofuentes in which Basque given names are listed.