During the Neolithic, there took place significant changes in techniques and industries (pottery and stone polishing), in the way of life and subsistence (agriculture, livestock and an emerging town planning that consisted of small villages with grouped huts), as well as in iconography and funeral rites. Those changes were brought massively and in a short period of time in the Near and Middle East ('the Neolithic revolution'), but in southwest Europe and therefore, in the ancient Basque Country, the changes were introduced more slowly and at longer intervals.

The most important Neolithic sites of the Basque territory are located in the  following caves: Areatza, Santimamiñe and Kobaederra (Biscay), Marizulo (Guipúzcoa), Fuente Hoz and Montico de Txarratu (Álava), Aizpea, Zatoia and Urbasa II (Navarre). Finally, there is the site of Abauntz (Muliña, coast of Labourd, France), where large seafood gathering picks have been found.

following caves: Areatza, Santimamiñe and Kobaederra (Biscay), Marizulo (Guipúzcoa), Fuente Hoz and Montico de Txarratu (Álava), Aizpea, Zatoia and Urbasa II (Navarre). Finally, there is the site of Abauntz (Muliña, coast of Labourd, France), where large seafood gathering picks have been found.

The Early Neolithic (from 4,500 to 4,000 B.C.) started with a few innovations that later were expanded in the Middle Neolithic (from 4,000 to 3,300 B.C.), together with livestock. The Late Neolithic (from 3,300 B.C. to the beginning of the Chalcolithic) brought along the megalithic funeral rites and there took place an expansion of agriculture and livestock, followed by settlements in the open.

The oldest pottery of the Basque Country (with no decoration) come from Zatoia (Navarre) and Fuente Hoz (Álava), which are dated between 4,400 and 4,000 B.C.. There are also fragments of cardium pottery (decorated by means of the impression of a cockle shell in the clay) that belong as well to the Early Neolithic, which were recovered from Peña Larga (Álava). The beakers decorated with fine applique or incisions that were performed during Middle Neolithic, come from Los Husos (Álava), Areatza (Biscay) and Marizulo (Guipúzcoa).

Around 4,000 B.C., the occupants of Zatoia hunted boars and to a lesser extent deers, mountain goats, roe deers and some horses, bovines and Pyrenean mountain goats. The people that inhabited Aizpea combined the hunting of those species and the fishing in the neighbouring river Irati. The domestic animals did not appear in the Basque Country until Middle Neolithic (Fuente Hoz, Abauntz and Marizulo): the livestock remains are always a minority with respect to those of wild animals. Only during the Late Neolithic (Los Husos and Arenaza) the stock of meat from domestic animals overcame the provisions from hunting. The first flocks were of sheep and goats and then bovine and sow.

In the Late Neolithic, there arose the use of instruments in order to take advantages of vegetal resources: the silex blades, which were used in harvesting and the portable mills (note that those tools would especially abound in the Chalcolithic period). In Middle and Late Neolithic, there were used axes and polished stone adzes for woodworking.

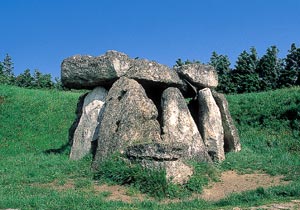

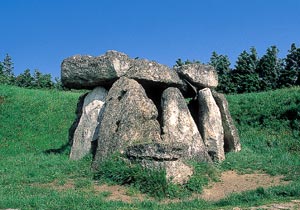

The Neolithic custom of burying the dead in the floor of the caves (as in Marizulo, Fuente Hoz and Aizpea) is gradually replaced since the end of this period, by collective deposits in the interior galleries of the cave (as Kobaederra in Biscay, Gobaederra and Peña Larga in Álava, Urtao II in Guipúzcoa as well as La Peña and Hombres Verdes in Navarre) and above all, in dolmens. In this method, the  dead were arranged in the burial chambers in an orderly way, and they were also adorned with pendants of bone and stone. Weapons, vessels and other utensils also accompanied them on their last voyage.

dead were arranged in the burial chambers in an orderly way, and they were also adorned with pendants of bone and stone. Weapons, vessels and other utensils also accompanied them on their last voyage.

There are listed around seven hundred dolmens in the cataloque of megalithic sites of the Basque Country (except tumular monuments) and almost a half of them are located in Navarre. The use of dolmens extended for nearly two thousand years: the first ones were built in the Late Neolithic (the most ancient dolmens date from 3,200 B.C. and are located in the region of La Rioja Alavesa) and their greatest expansion took place during the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze. Some of them were still used during the Middle Bronze until 1,500-1,300 B.C.. The biggest Basque dolmen is the one of Aizkomendi. The single-chamber dolmens (with a main single room which could be square or polygonal) constitute the majority of them. On the other hand, there are other dolmens which feature a corridor that precedes the chamber and with covered galleries, as in the case of the monuments of Artajona in Navarre, San Martín and El Sotillo in La Rioja.

The metallurgical development in southwest Europe has been defined on three stages: Chalcolithic (Eneolithic or Copper Age), from 2,500 to 1,800 B.C.; Broze Age (early period from 1,800 to 1,500 B.C., middle period from 1,500 to 1,200 B.C. and the late period, in transition to the Iron Age, from 1,200 to 900 / 850 B.C.): Iron Age (from 900 / 850 B.C. onwards).

Tools, weapons and domestic utensils made of copper and bronze abound in the Chalcolithic as well as in the Bronze Age, like punches or awls, different types of axes (flat, flanged, socketed, and so on), daggers with a prepared base to place the handle, arrow heads, bracelets, rings, beads of a necklace.... In the Chalcolithic, the hammering of grains of gold produced wires or tags that served as jewels, like the ones that were found in the dolmens of Trikuaizti (Guipúzcoa) and Sakulo (Navarre).

The caves, as places to live, were gradually abandoned and huts were built in the open during the Late Neolithic and the Chalcolithic. The most outstanding places to live during the Chalcolithic and the Bronze Age were the caves of Solacueva and Los Husos (Álava), as well as the rock shelter of Monte Aguilar in Las Bárdenas Reales (Navarre). Regarding the settlements in the open, there is an extended list of hut floors and workshops of stone tools that are as interesting as La Renque in Treviño (Burgos) and the workshops of Álava, Middle Navarre and the Riverbank.

During the Middle and Late Bronze, the huts were grouped and they were provided with common elements such as water wells, silos or walls. In some of the incipient villages of Navarre and Álava, there are ceramics and metal utensils (flat rivetted daggers, arrow heads and several bronze ornaments) in which the archaeologists see the influence of La Meseta in the south of the Basque lands.

During the Middle and Late Bronze, the huts were grouped and they were provided with common elements such as water wells, silos or walls. In some of the incipient villages of Navarre and Álava, there are ceramics and metal utensils (flat rivetted daggers, arrow heads and several bronze ornaments) in which the archaeologists see the influence of La Meseta in the south of the Basque lands.

The Bell-Beaker pottery appears in the funerary deposits of the Chalcolithic period (from 2,500 to 1,800 B.C.): the 'Maritime' and the 'Corded' styles are present in the northern areas of the Basque Country (the dolmens of Pagobakoitza, Gorostiaran and Trikuaizti), while the Bell-Beakers of 'Continental' style have been found in several dolmens that are located near the Ebro riverbank (San Martín, Sotillo, Los Llanos...), as well as the sites of La Renque (Treviño, Burgos), Tudela and Las Bárdenas Reales (Navarre).

The excavation of the funerary deposits inside the caves (Lumentxa in Biscay, Urtiaga and other caves in Guipúzcoa, as well as Gobaederra, Las Calaveras and Fuente Hoz in Álava, among others) or in dolmens (Aralar in Navarre, Kuartango in Álava, Aizkorri in Guipúzcoa, some other sites in La Rioja...) has provided a considerable number of human remains of the time. The sample, which covers about two millennia between the Late Neolithic and the end of the Bronze Age, has allowed the archaeologists to determine the predominance of two main racial types: the Western-Pyrenean type or Basque (13), from the Navarrese mountains and the coast of Guipúzcoa and Biscay, and the Gracefull Mediterranean type, recovered from the southern areas. Furthermore, there are other minority groups (Paleomorphics, Alpines...), and remains of ancient ethnic groups or from distant countries (such as the Dinaric-Armenian individuals that were found in the Navarrese cave of Los Hombres Verdes).

(13) The Western-Pyrenean race or Basque: it is the racial type that arose as a consequence of a local evolution of the Cro-Magnon man. Anthropology includes the Basque type in the Caucasian race, and its physical characteristics are the following ones:

Orthognathism: the profile of the face is straight, excluding the nose. Dolichocephalic individuals with a low cranial vault (in the Northern Basque Country or Iparralde, the dolichocephaly condition can be attenuated and even turned into brachicephaly by influence of the Alpine type). The face has a great vertical development in relation to the length of the mouth. Maxillary narrowness and mesocephally: Triangle-shaped face with large temples. The occipital hole is oblique: the leading edge is inside or sunken. The lower jaw is rather narrow and the chin is small. The face is very high as well as the nose, which is very prominent and often causes a convex profile. Regarding the hair, the dark-haired people prevail over brown-haired individuals. Blondes and redheads represent a minority and they were originated by means of miscegenation. The eyes are rather small and wide open: brown and blue eyes predominate over the green and grey ones. Commonly, the individuals of Basque type differ from their Latin neighbours by their greater height and corpulence, to which certain tendency towards a lighter skin coloration must be added.

Orthognathism: the profile of the face is straight, excluding the nose. Dolichocephalic individuals with a low cranial vault (in the Northern Basque Country or Iparralde, the dolichocephaly condition can be attenuated and even turned into brachicephaly by influence of the Alpine type). The face has a great vertical development in relation to the length of the mouth. Maxillary narrowness and mesocephally: Triangle-shaped face with large temples. The occipital hole is oblique: the leading edge is inside or sunken. The lower jaw is rather narrow and the chin is small. The face is very high as well as the nose, which is very prominent and often causes a convex profile. Regarding the hair, the dark-haired people prevail over brown-haired individuals. Blondes and redheads represent a minority and they were originated by means of miscegenation. The eyes are rather small and wide open: brown and blue eyes predominate over the green and grey ones. Commonly, the individuals of Basque type differ from their Latin neighbours by their greater height and corpulence, to which certain tendency towards a lighter skin coloration must be added.

The chromosome and serological studies have revealed other significant differences, especially the extraordinary frequency of Rh-negative individuals. The Rh-negative factor is common to all the human communities of prehistoric origin that have lived isolated for thousands of years. The Rh-positive individuals, who are a majority today, arose by means of a relatively recent mutation in humanity.

Anthropologists indicate that the Western-Pyrenean type was much more spread in ancient times than nowadays. Outside the Basque Country, the somatic influence of this racial type, although mixed and attenuated, is still present southwards in several regions of Castile; eastwards, in several valleys of the Pyrenees up to Andorra and northwards, through the Atlantic coast line. Furthermore, it has been pointed out that the presence of this type would very probably be even in Wales (United Kingdom), as the remains of the Proto-Basque expansion in Europe during the Magdalenian.

Today, the Spanish and Portuguese population is of Mediterranean type for the most part. It has been possible to observe that there were individuals of Mediterranean and Alpine types in the south of the Basque Country since the Neolithic. At present, the Mediterranean type is also in the majority in the main Basque cities due to the migration of the peninsular Latin people to the Basque territories, mostly since the 20th century. In the case of Iparralde (Northern Basque Country) and especially in its coastal area, there are individuals of Alpine type (that come from central and eastern areas of France) together with the Mediteranean type, as well as people of Nordic type (that come from northern France), due to past and current Latin migrations from central, eastern and northern France. On the contrary, the Basque type is common in the rural areas of Northern Euskadi, inland Iparralde and northern half of Navarre, due to its isolation regarding the migratory flows.

However, the future Basques will not only be Caucasians. Since the beginning of the 21st century it has begun an intense process of immigration from Latin America (Amerindians of different types), from central Africa (Guinean and Sudanese types), from northern Africa (Berber and Southeastern Caucasian types), from eastern Europe (Western-Baltic, Nordic, Alipine and Dinaric Caucasians) as well as Mongoloids from central Asia. Those groups are already settling not only in the main cities, but also in the rural areas, what will cause that the future Basque society turns into a mixed, multiracial and multicultural society.

During the transition to the Ancient history (or Proto-History), two stages of the Iron Age are considered: the first one, from 900/850 to 500/450 B.C. (Iron I) and the second one, which goes from then to the development of Romanisation (Iron II). Around 1,000-900 B.C., cultural innovations of foreign origin widespread through southwest Europe: techniques and decoration of pottery and metal objets, buildings, funerary rites, onomastics and toponymy, religious beliefs and artistic symbology. In those remains, it is possible to observe some different influences over the population that inhabited the Basque Country at that time: the culture of 'Las Cogotas' from La Meseta, the Celtic peoples from the other side of the Pyrenees and other groups from Aragón and Catalonia. They were rural people that made a living in agriculture and livestock (beef, sheep and pig farming).

During the transition to the Ancient history (or Proto-History), two stages of the Iron Age are considered: the first one, from 900/850 to 500/450 B.C. (Iron I) and the second one, which goes from then to the development of Romanisation (Iron II). Around 1,000-900 B.C., cultural innovations of foreign origin widespread through southwest Europe: techniques and decoration of pottery and metal objets, buildings, funerary rites, onomastics and toponymy, religious beliefs and artistic symbology. In those remains, it is possible to observe some different influences over the population that inhabited the Basque Country at that time: the culture of 'Las Cogotas' from La Meseta, the Celtic peoples from the other side of the Pyrenees and other groups from Aragón and Catalonia. They were rural people that made a living in agriculture and livestock (beef, sheep and pig farming).

There are several villages which stand out from the wide list of the Iron Age sites that we currently know: Arrola and Gastiburu in Biscay, Intxur and Buruntza in Guipúzcoa, El Alto de la Cruz of Olaritzu and Berbeia in Álava and finally, La Custodia and El Castillar of Mendabia in Navarre. Regarding the mountainous areas of Iparralde, there are fortified enclosures (popularly known as 'castles' or 'Caesar's fields') such as the ones of Gazteluzarra of Irisarri and Arhansus.

The houses are organised in blocks and streets, and some villages have walls that sometimes are built according to a concentric pattern, where the walls are separated by moats. There are houses with a rectangular base and a shed or gabled roof (an average area of 80 square metres, as in the case of La Hoya in Álava, and up to 110 square metres as in Alto de la Cruz, Navarre), as well as circular buildings with a conical roof (between 20 and 30 square metres), as in the case of the villages Peñas de Oro and Castillo de Henaio in the territory of Álava. Their construction is very careful and includes a foundation structure or podium over which the walls are built. Those walls could be made of stone or adobe that were bonded with wooden bases and sometimes, re-covered with clay. The houses were provided with benches, fireplaces, silos and ovens. The buildings from El Alto de la Cruz (Cortes, Navarre) even had landers and garrets to keep their home goods, as well as cages for domestic animals. There are other utensils which are part of the furniture at the time, such as containers for water or grain, cooking ceramics, loom weights, portable mills and andirons.

Bracelets, fibulae, belt brooches and buttons made of copper or bronze, little ceramic boxes and luxurious vessels (decorated by excision, grooved or painted), some little idols and dolls that were made of clay and several jewels are part of the personal belongings of those people. The Axtroki bowls (two semi-spherical pieces that were embossed in gold), recovered in Eskoriatza (Guipúzcoa), date from the centuries 8th-7th B.C. and are a good example of the decorative arts from that period.

Bracelets, fibulae, belt brooches and buttons made of copper or bronze, little ceramic boxes and luxurious vessels (decorated by excision, grooved or painted), some little idols and dolls that were made of clay and several jewels are part of the personal belongings of those people. The Axtroki bowls (two semi-spherical pieces that were embossed in gold), recovered in Eskoriatza (Guipúzcoa), date from the centuries 8th-7th B.C. and are a good example of the decorative arts from that period.

In the Iron Age, the custom of cremating the dead became widespread. The ashes were kept in ceramic urns that later were placed in small flagstone enclosures (cists) or under tumuli (mounds of earth). The cremation tombs were grouped in urnfields close to the main villages, as the Navarrese necropolises of La Torraza of Valtierra and La Atalaya of Cortes, as well as La Hoya (Álava).

Regarding the Pyrenean area (in the limit between Guipúzcoa and Navarre, as well as Navarre and the northern territories), the ashes of the deceased were buried in a tumulus of earth and stones, or in a hollow defined by a stone circle or cromlech (known as 'baratzak' [barátsak]). The Carbon 14 dating of some tombs from Iparralde shows their use along the first millennium B.C.., and the fact that they were still used in the Middle Ages in some cases, due to remains of the rituals that were performed in the ancient Basque religion.

In the plain of Álava (the sites of Landatxo, La Teja, El Fuerte, El Batán, Mendizorrotza and Salbatierrabide), there are 'cremation holes' that were dug in the ground. They contain remains of animals, ceramics and metal objects which date between Late Bronze and Iron II..

The animal figures painted in red from Peña del Cantero (Etxauri, Navarre), or engraved, as in La Peña del Cuarto (Leartza, Navarre) belong to the Middle Bronze. The inner area of several caves located in Álava (Solacueva, Los Moros in Atauri, Latzaldai and Liziti) show several figures of hunters and animals that were made in black and in a very schematic way: they are attributed to the Iron Age.

During the Iron II period, vessels were made on a potter's wheel. The Celtiberian-style paintings found in the Navarrese sites of La Custodia, Castejón, Leguín and Sansol, as well as La Hoya in Álava were made around the years 350-300 B.C.. Furthermore, there have been recovered several iron farming tools and horse tacks from the final levels of La Hoya (Álava), Etxauri (Navarre) and in the late village of San Miguel de Atxa (Álava). Those villages and others from different territories would gradually embrace the Romanisation.

Share this page!

The History of the Basque Country continues on the following page >> The Basque Tribes

following caves: Areatza, Santimamiñe and Kobaederra (Biscay), Marizulo (Guipúzcoa), Fuente Hoz and Montico de Txarratu (Álava), Aizpea, Zatoia and Urbasa II (Navarre). Finally, there is the site of Abauntz (Muliña, coast of Labourd, France), where large seafood gathering picks have been found.

following caves: Areatza, Santimamiñe and Kobaederra (Biscay), Marizulo (Guipúzcoa), Fuente Hoz and Montico de Txarratu (Álava), Aizpea, Zatoia and Urbasa II (Navarre). Finally, there is the site of Abauntz (Muliña, coast of Labourd, France), where large seafood gathering picks have been found.  dead were arranged in the burial chambers in an orderly way, and they were also adorned with pendants of bone and stone. Weapons, vessels and other utensils also accompanied them on their last voyage.

dead were arranged in the burial chambers in an orderly way, and they were also adorned with pendants of bone and stone. Weapons, vessels and other utensils also accompanied them on their last voyage. During the Middle and Late Bronze, the huts were grouped and they were provided with common elements such as water wells, silos or walls. In some of the incipient villages of Navarre and Álava, there are ceramics and metal utensils (flat rivetted daggers, arrow heads and several bronze ornaments) in which the archaeologists see the influence of La Meseta in the south of the Basque lands.

During the Middle and Late Bronze, the huts were grouped and they were provided with common elements such as water wells, silos or walls. In some of the incipient villages of Navarre and Álava, there are ceramics and metal utensils (flat rivetted daggers, arrow heads and several bronze ornaments) in which the archaeologists see the influence of La Meseta in the south of the Basque lands.  Orthognathism: the profile of the face is straight, excluding the nose. Dolichocephalic individuals with a low cranial vault (in the Northern Basque Country or Iparralde, the dolichocephaly condition can be attenuated and even turned into brachicephaly by influence of the Alpine type). The face has a great vertical development in relation to the length of the mouth. Maxillary narrowness and mesocephally: Triangle-shaped face with large temples. The occipital hole is oblique: the leading edge is inside or sunken. The lower jaw is rather narrow and the chin is small. The face is very high as well as the nose, which is very prominent and often causes a convex profile. Regarding the hair, the dark-haired people prevail over brown-haired individuals. Blondes and redheads represent a minority and they were originated by means of miscegenation. The eyes are rather small and wide open: brown and blue eyes predominate over the green and grey ones. Commonly, the individuals of Basque type differ from their Latin neighbours by their greater height and corpulence, to which certain tendency towards a lighter skin coloration must be added.

Orthognathism: the profile of the face is straight, excluding the nose. Dolichocephalic individuals with a low cranial vault (in the Northern Basque Country or Iparralde, the dolichocephaly condition can be attenuated and even turned into brachicephaly by influence of the Alpine type). The face has a great vertical development in relation to the length of the mouth. Maxillary narrowness and mesocephally: Triangle-shaped face with large temples. The occipital hole is oblique: the leading edge is inside or sunken. The lower jaw is rather narrow and the chin is small. The face is very high as well as the nose, which is very prominent and often causes a convex profile. Regarding the hair, the dark-haired people prevail over brown-haired individuals. Blondes and redheads represent a minority and they were originated by means of miscegenation. The eyes are rather small and wide open: brown and blue eyes predominate over the green and grey ones. Commonly, the individuals of Basque type differ from their Latin neighbours by their greater height and corpulence, to which certain tendency towards a lighter skin coloration must be added.  During the transition to the Ancient history (or Proto-History), two stages of the Iron Age are considered: the first one, from 900/850 to 500/450 B.C. (Iron I) and the second one, which goes from then to the development of Romanisation (Iron II). Around 1,000-900 B.C., cultural innovations of foreign origin widespread through southwest Europe: techniques and decoration of pottery and metal objets, buildings, funerary rites, onomastics and toponymy, religious beliefs and artistic symbology. In those remains, it is possible to observe some different influences over the population that inhabited the Basque Country at that time: the culture of 'Las Cogotas' from La Meseta, the Celtic peoples from the other side of the Pyrenees and other groups from Aragón and Catalonia. They were rural people that made a living in agriculture and livestock (beef, sheep and pig farming).

During the transition to the Ancient history (or Proto-History), two stages of the Iron Age are considered: the first one, from 900/850 to 500/450 B.C. (Iron I) and the second one, which goes from then to the development of Romanisation (Iron II). Around 1,000-900 B.C., cultural innovations of foreign origin widespread through southwest Europe: techniques and decoration of pottery and metal objets, buildings, funerary rites, onomastics and toponymy, religious beliefs and artistic symbology. In those remains, it is possible to observe some different influences over the population that inhabited the Basque Country at that time: the culture of 'Las Cogotas' from La Meseta, the Celtic peoples from the other side of the Pyrenees and other groups from Aragón and Catalonia. They were rural people that made a living in agriculture and livestock (beef, sheep and pig farming). Bracelets, fibulae, belt brooches and buttons made of copper or bronze, little ceramic boxes and luxurious vessels (decorated by excision, grooved or painted), some little idols and dolls that were made of clay and several jewels are part of the personal belongings of those people. The Axtroki bowls (two semi-spherical pieces that were embossed in gold), recovered in Eskoriatza (Guipúzcoa), date from the centuries 8th-7th B.C. and are a good example of the decorative arts from that period.

Bracelets, fibulae, belt brooches and buttons made of copper or bronze, little ceramic boxes and luxurious vessels (decorated by excision, grooved or painted), some little idols and dolls that were made of clay and several jewels are part of the personal belongings of those people. The Axtroki bowls (two semi-spherical pieces that were embossed in gold), recovered in Eskoriatza (Guipúzcoa), date from the centuries 8th-7th B.C. and are a good example of the decorative arts from that period.